The attribute table for the base zoning layer of the Zoning Atlas has nearly 80 fields, which fall into the following categories:

- Identifying information, which includes the name of the municipality, the name and abbreviation the municipality has assigned to that zone, and the standardized zone ID.

- Use information, including fields that describe what uses are allowed in the zone, for example, whether multifamily housing (defined as 2+ units) is allowed by special permit or by-right.

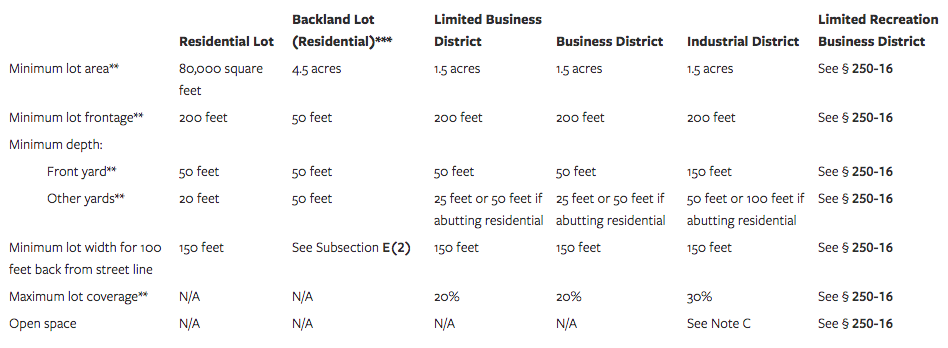

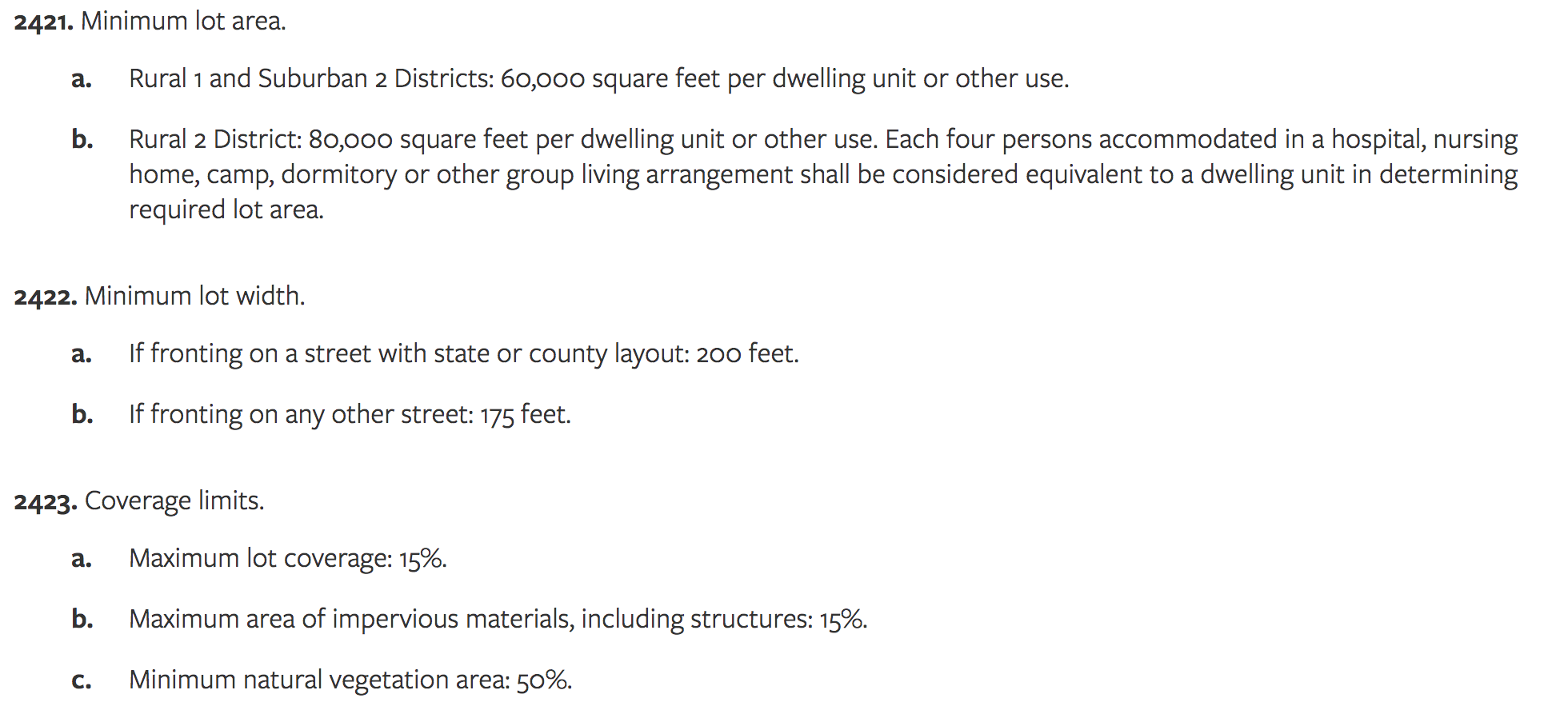

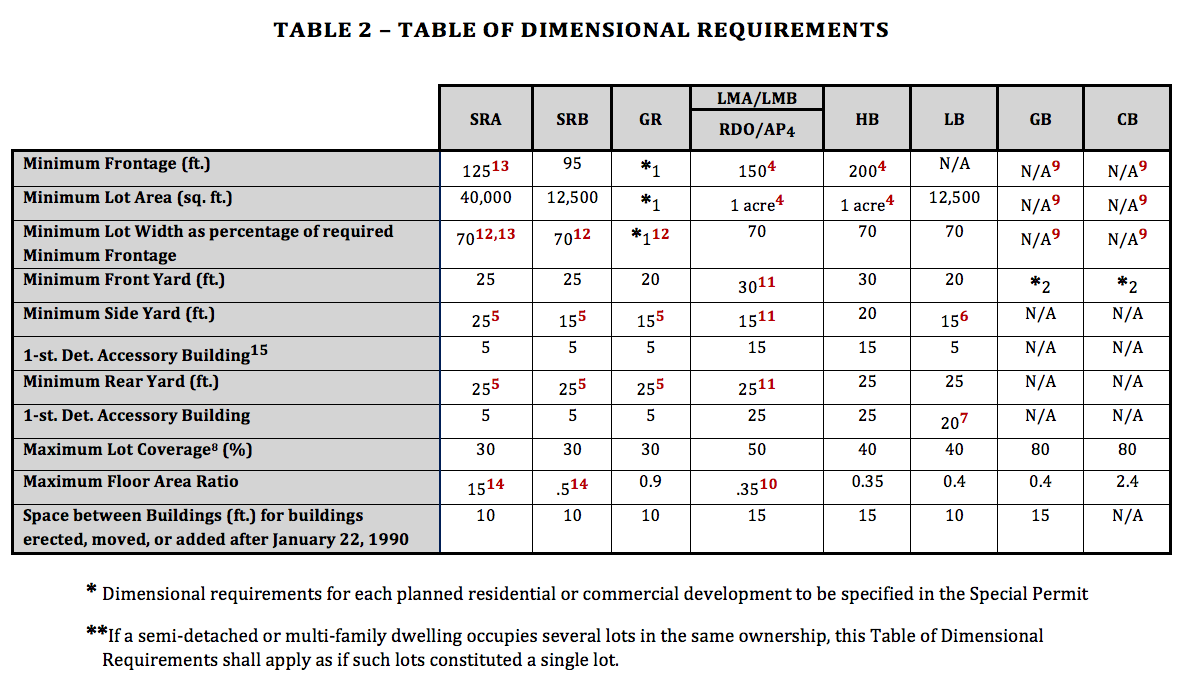

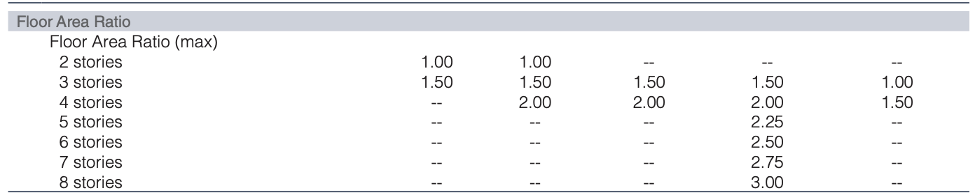

- Dimensional regulations, including the core attributes of Minimum Lot Size, Maximum Height, Maximum Dwelling Units per Acre, and FAR. Since not all of these values are specified in the zoning code, this group of fields also includes other requirements more commonly specified and the intermediate calculations used by MAPC to arrive at the final estimates for each of the core attributes.

- Text fields capture additional complexities about the regulations and additional details about our methods. For example, there is an open text field that pairs with each Override Value to record the reason one was needed.

- Metadata, such as last edit date and revision history information.

Key attributes in the Zoning Atlas are summarized below. More details on how they were calculated is available in the technical appendix.

Zone Use Type (ZO_USETY): This field describes what uses – (1) Residential, (2) Non-residential, (3) Residential and Non-residential (mixed use), or (4) Open Space – are allowed in the zone by right, regardless of the zone name or zone description. Zone Use Type is populated for all zones in the Atlas.

Multifamily Fields (MULFAM2, MULFAM3_4, MULFAM5_19, MULFAM20_): This series of fields describes whether two, three to four, five to 19, and 20 or more residential units are allowed on a lot within a given zone, and if so, whether they are allowed by (1) Special Permit or (2) By right. It is currently the only field in the database that captures special permit information.

Minimum Lot Size (MINLOTSIZE): This field estimates the minimum lot area required for a developable parcel. Where multiple minimums are stated based on different uses, the recorded value corresponds to the use with the greatest allowable as-of-right density. MINLOTSIZE is populated for approximately 80% of the zones in the Atlas.

Maximum Percent Lot Coverage (PCTLOTCOV): This field specifies the maximum percent of the lot that can be covered by structures. As with the other dimensional regulations, the published value in the Atlas corresponds with the dimensional regulations of the greatest density use. PCTLOTCOV is populated for approximately 60% of the zones in the Atlas.

Minimum Land Area per Dwelling Unit (LApDU): This field specifies the minimum amount of lot area required for each dwelling unit. As with the other dimensional regulations, the published value in the Atlas corresponds with the dimensional regulations of the greatest density use, and maximum utilization of a lot. LApDU is populated for approximately 40% of the zones in the Atlas where residential development is allowed by right.

Maximum Building Height (MAXHEIGHT): This field specifies the maximum allowable building height in feet. As with the other dimensional regulations, the published value in the Atlas corresponds with the dimensional regulations of the greatest density use. MAXHEIGHT is populated for approximately 80% of the zones in the Atlas.

Maximum Building Floors (MAXFLRS): This field specifies the maximum allowable building floors, or stories. As with the other dimensional regulations, the published value in the Atlas corresponds with the dimensional regulations of the greatest density use. MAXFLRS is populated for approximately 50% of the zones in the Atlas.

Maximum Dwelling Units (MAXDU): This field describes the maximum number of dwelling units allowed on a lot by right. As with the other dimensional regulations, the published value in the Atlas corresponds with the dimensional regulations of the greatest density use. MAXDU is populated for approximately 50% of the zones in the Atlas where residential development is allowed by right.

Dwelling Units per Acre (DUpAC): This field is an estimate of the maximum allowable housing density in terms of dwelling units per acre. DUpAC is based on actual zoning specifications for approximately 20% of the zones in the Atlas where residential development is allowed by right, and has been estimated for an additional 70% of such zones.

Floor area Ratio (FAR): This field estimates the maximum FAR allowed in a zone by right. It is either reported (based on zoning code) or estimated for approximately 40% of all districts.

In the base zoning attribute table, there are actually multiple attributes that correspond to each of the measures described above, including values sourced directly from the zoning code, those that are estimated from other values, and those that are asserted based on analyst interpretation. There are also fields that describe how the final estimate was made and an "effective value" that represents MAPC's best estimate based on the information collected and analysis conducted.

For more detail on how the fields were calculated, please see the technical appendix.